Morita Shiryū: Bokujin

-

Shibunkaku is pleased to announce Morita Shiryū: Bokujin, an exhibition that brings into the spotlight an artist who left his distinctive mark on modern art and irrevocably changed the landscape of Japanese postwar calligraphy.

In the early 1950s, calls for reformation grew increasingly stronger from within the circles of calligraphy, one of the traditional arts. The emerging avant-garde movement of calligraphy, incorporating inspiration from American and European abstract painting, soon began to garner recognition on the stages of the international art world. At the center of this unprecedented endeavor connecting East and West, and fusing the traditional art of calligraphy with modern abstract painting, was the calligrapher Morita Shiryū. In a balancing act of combining a time-honored art with his strong intent to innovate, Morita breathed new life into calligraphy and pushed it into the attention of the world.

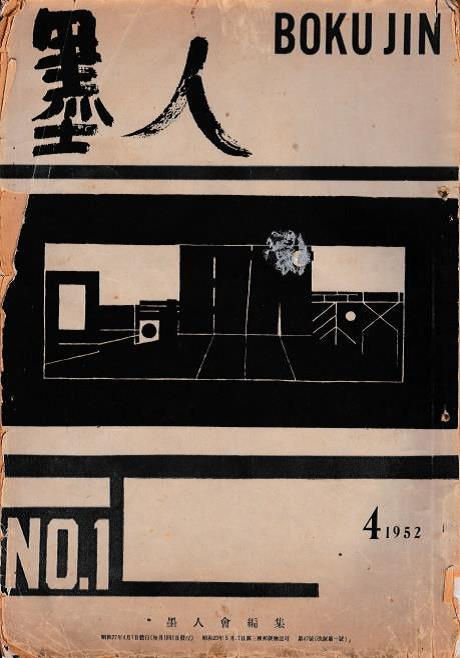

The journal Bokubi (Beauty of Ink), founded by Morita in 1951 and running for about 300 issues, was a new, one-of-a-kind platform for the arts that in the 1950s and 1960s encouraged the exchange among artists regardless of genre or country of origin. The art association Bokujinkai (Ink People), established in 1952 in Kyoto by Morita and four like-minded artists to challenge the outdated conventionality of Japanese calligraphy circles and re-establish the field as a genre of modern art, grew into the most representative group of Japanese postwar avant-garde calligraphy, and in the 1960s extended its activities internationally.

Founding members of Bokujinkai: (left to right) Morita, Sekiya Yoshimichi, Inoue Yūichi, Nakamura Bokushi. Sep 24, 1952.

Questioning the essence of calligraphy, Morita built on the theoretical foundations of Iijima Tsutomu, a scholar of aesthetics of Kyoto University, and sought to connect these with his own practice and Hisamatsu Shin’ichi (a philosopher from the Kyoto School)’s theories on Zen, declaring that “sho (calligraphy) is the site of writing characters, which manifests the dynamic movements of our inner being.” The self becomes one with the constraining factors of characters, brush and ink, and the art of calligraphy unfolds on the paper “in a single movement that is unified and unique,” its visible traces crystallizing the calligraphic shape and melding into the meditative realm of “absolute nothingness” that is characteristic of Zen philosophy. It was a whole new vision of calligraphy as an art.

In the first half of the 1950s, the abstract painter and Gutai leader Yoshihara Jirō, who like Morita had been involved in Genbi (Contemporary Art Discussion Group), argued that the potential of calligraphy was limited by its dependency on characters, indeed calligraphy should overcome these limitations by shaking free from characters altogether. Yet for Morita, characters were not a limitation, but to the contrary it was especially the fact that calligraphy depended on them as its inherent framework that allowed it to achieve its spatial expanse and unique temporality. The reliance on characters therefore was integral to calligraphy.

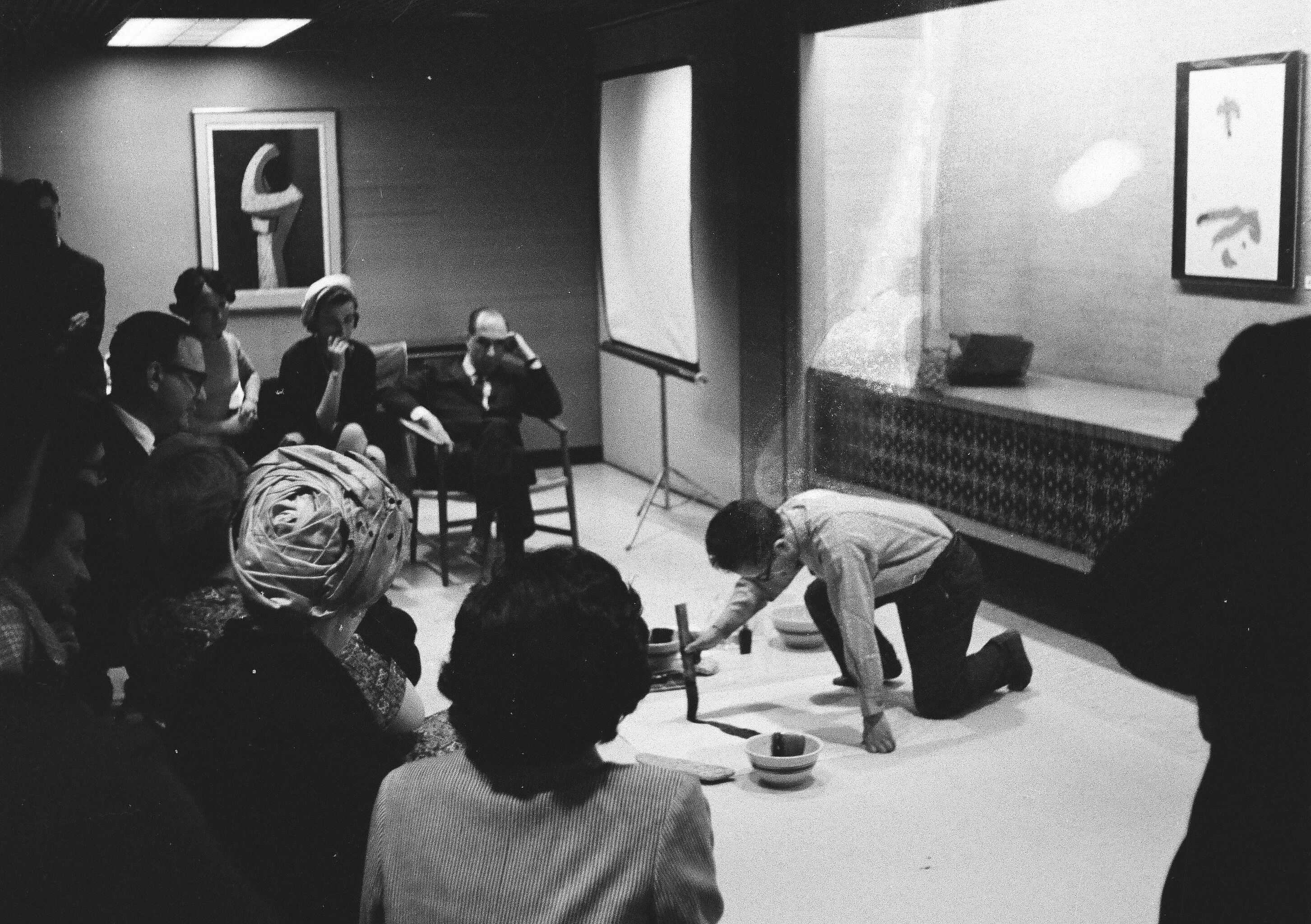

In 1963, the year of his first international solo exhibition, Morita traveled through the United States and four European countries, where he lectured on the “Appeal of a Japanese Calligrapher,” gave calligraphy demonstrations, and presented a movie that showed Japan’s avant-garde calligraphers at work. These activities were well received among the American and European abstract expressionists. Within a short time after the war, Morita Shiryū succeeded in elevating Japanese calligraphy, a traditional art from embedded in East Asian culture, to the world stage by transforming his words and body movements into artistic expression. While the current cultural climate is fundamentally different from the postwar era, we believe that in a world of rapidly changing values and conditions there is a deeper meaning in turning one’s attention to this artist whose work embodies a passionate quest to grasp the more essential things in art and life.

The present exhibition centers on Morita’s calligraphy from the 1960s, when he established himself as part of the international modern art world and was widely active at home and abroad, but also includes works as early as from the 1940s up to the 1980s and 1990s. In addition to Morita’s works, this exhibition includes a documentary movie, showing scenes from the studio of the calligrapher that illustrate the artist’s approach of converting movements of the whole body into form, and examples from Bokubi, the journal that Morita founded and edited, showcasing his skills as an organizer, editor and art theorist.

Ijima Tsutomu (left) at the Bokujin Exhibition of 1954.

Hisamatsu Shini’ichi at the Bokujin Exhibition of 1954.

In a world of rapidly changing values, beliefs, and conditions after the spread of coronavirus people are turning their attention to search for the self that is on the inside. It is time to shed light on Morita who, a half century ago, succeeded to elevate Japanese calligraphy, a traditional art from embedded in East Asian culture, to the world stage in the postwar years by transforming his words and body movements into artistic expression.

We’re excited to welcome you to Morita Shiryū: Bokujin.

Exhibition schedule

Kyoto

January 10 – January 23, 2021 | Shibunkaku

355 Motomachi, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto, Japan

Tel: +81-75-531-0001, Fax: +81-75-531-5533

*open all days

Tokyo

January 29 – February 13, 2021 | Shibunkaku Ginza

Ichibankan-Building 5-3-12 Ginza, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Tel: +81-3-3289-0001, Fax: +81-3-3575-4863

*open all days

Contact for inquiries: wanobi@shibunkaku.com

Sho is the site of

writing characters,

which manifests the

dynamic movements

of our inner being.

II. Overview

This exhibition centers on Morita’s calligraphy from the 1960s, when he established himself as part of the international modern art world and was widely active at home and abroad, but also includes works as early as from the 1940s up to the 1980s and 1990s.

In the first half of the 1950s, the abstract painter and Gutai leader Yoshihara Jirō, who like Morita had been involved in Genbi (Contemporary Art Discussion Group), argued that the potential of calligraphy was limited by its dependency on characters, indeed calligraphy should overcome these limitations by shaking free from characters altogether. Yet for Morita, characters where not a limitation, but to the contrary it was especially the fact that calligraphy depended on them as its inherent framework that allowed it to achieve its spatial expanse and unique temporality. The reliance on characters therefore was integral to calligraphy.

Yoshihara Jirō, Osawa Gakyu, and Morita (left to right) at the "Calligraphy and Abstract Painting" roundtable discussion, 1953.

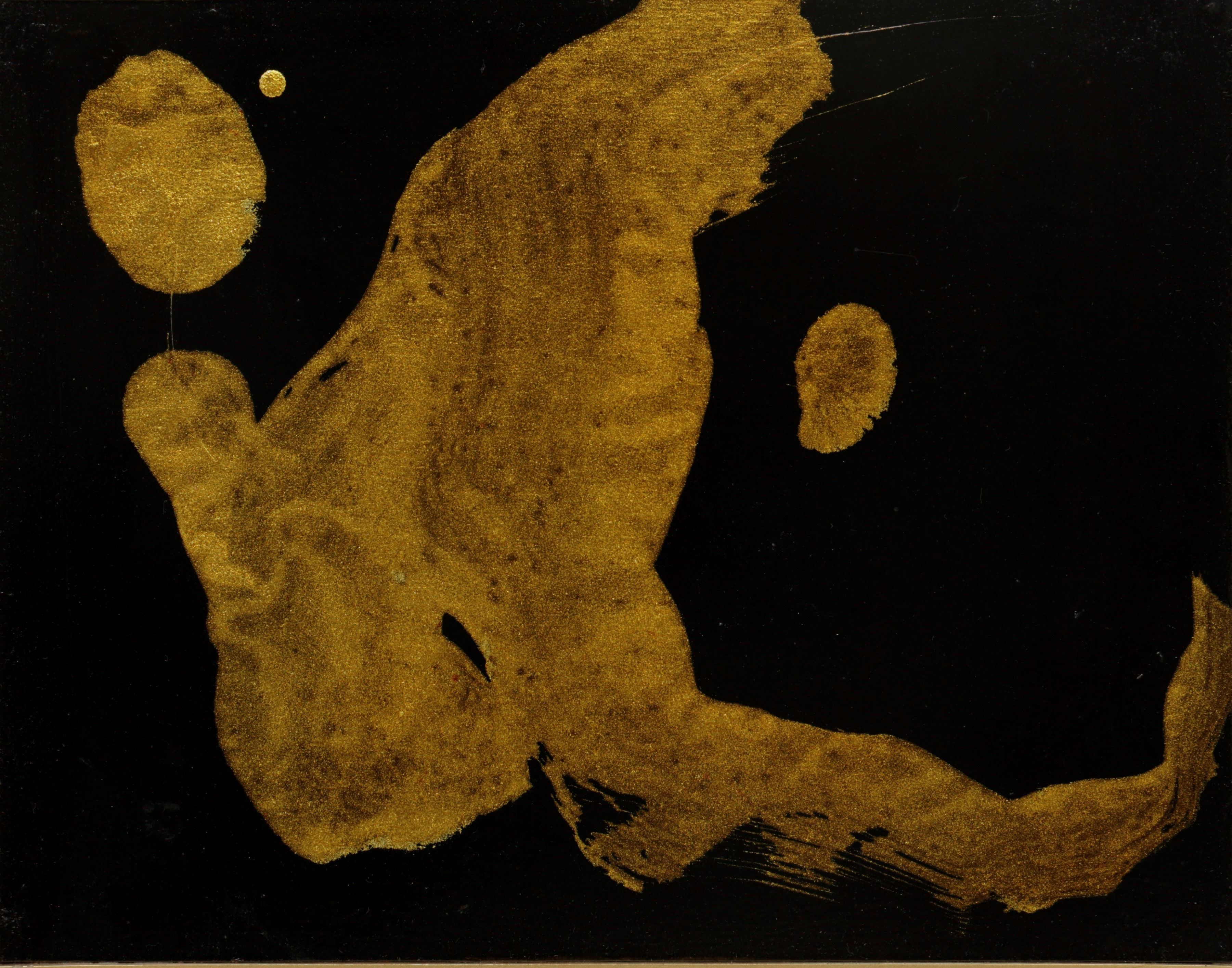

Calligraphy is considered a two-dimensional art of ink on paper, yet through the movement and rhythm of the brush, the tone of the ink, its gradation and contrast, its saturation and the addition of new materials and techniques it gains color and an almost three-dimensional presence. Morita progressed from traditionally ground ink of the early years to ink enhanced with lamp black or other new materials, he used synthetic glues instead of nikawa (animal glue) as an adhesive, and eventually experimented with aluminum flake pigment mixed with nikawa or glue medium over black paper, covered in lacquer for his signature shikkin technique. The results of Morita’s extraordinary versatility are a must-see.

Work details, top row left to right: Shadow from the Future (ink on paper, 1949); Sō (ink on paper, 1954); Usobuku (ink on paper, 1963).

Second row left to right: Kanzan (aluminum flake pigment and lacquer on paper, 1969); En (aluminum flake pigment on paper, c. 1969); Asa (ink on paper, c. 1970)

Calligraphy demonstration: At the New York Artist's Club, 1963.

Calligraphy demonstration: At the New York Artist's Club, 1963.

Installation view: Myō/Setsugetsuka. Aluminum flake pigment and lacquer on paper, pair of framed works, 74 x 95 cm, 1964.

III. Chronology & Selected Exhibitions

Chronology

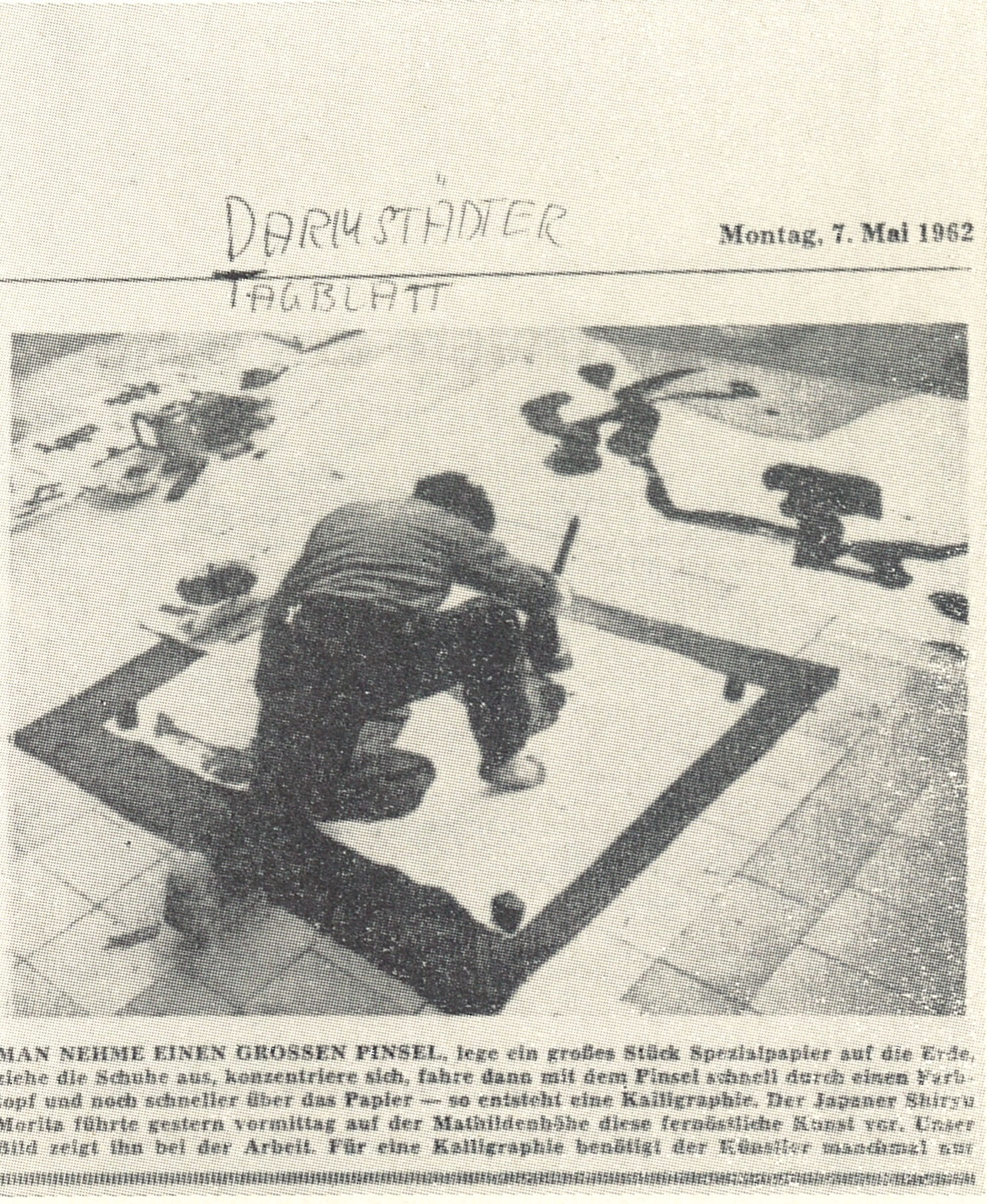

1912 Born in Toyooka City, Hyōgo Prefecture. 1937 Began to study calligraphy under Ueda Sōkyū. Moved to Tokyo. 1938 Received Minister of Education Award for Japan-Manchuria-China Exhibition. 1944 Evacuated to Toyooka. 1948 Launched Sho no bi (Beauty of Calligraphy) (–1952). 1950 Moved to Kyoto. Acquainted with Ijima Tsutomu and Hisamatsu Shin’ichi. 1951 Launched Bokubi (Beauty of Ink) (–1981). 1952 Co-founded the avant-garde calligraphers’ group Bokujinkai (Ink People Society) with Inoue Yūichi, Eguchi Sōgen, Nakamura Bokushi, and Sekiya Yoshimichi. 1962 Participated in cultural exchange in Germany at the invitation of the Germany government. 1963 Visited Europe and the US, lectured, demonstrated, and showed films on calligraphy. 1968 Hosted calligraphy for NHK broadcast program series for one year, staring in January. 1971 Published The Works of Shiryū Morita: Selected by the Artist. 1975 Published the exhibition catalog Morita Shiryū's Sho (Japanese Calligraphy). Published Modern Art Series, vol. 28: Sho and Ink Art. 1978 Received a Destinguished Contributor to the Fine and Applied Arts by Kyoto Prefecture. Resigned from Bokujinkai. 1980 Designated as a Person of Cultural Merit by the Kyoto City. Published In/Chiffres, works of Morita Shiryū and the French intellectual Roger Caillois. 1981 Launched Ryūmon (Gate of Dragon) (–1984). 1984 Established Soryusha as a center for the study of calligraphy. 1995 Received a Cultural Award by Hyōgo Prefecture. 1998 Passed away at the age of 86. 2000 Posthumously awarded the Medal with Dark Blue Ribbon.

Installation view: Morita Shiryū solo exhbition at Mi Chou Gallery, New York City, 1963.

Selected Exhibitions

1953 Salon of October. Paris: Galerie Craven. 1954 Japanese Calligraphy. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. 1st Bokujin Group Exhibition. Tokyo and Kyoto: Maruzen Gallery. 1955 Japan-America Abstract Arts. Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art.

Phases of Contemporary Art. Paris. Bokujin Group Exhibition. Paris: Galerie Colette Allendy; Brussels: Galerie Apollo. Contemporary Japanese Calligraphy: Art in Sumi. Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art; later traveled to Europe. 1957 Bokujin Group Exhibition. New York: World House Gallery. 1958 Development of Modern Japanese Abstract Painting. Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art. Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute. 1959 5th São Paulo Art Biennial. São Paulo. 1961 6th São Paulo Art Biennial. São Paulo. Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute. Modern Japanese Ink-painting. Traveling exhibition throughout the US. 1962 Meaning and Symbol: Masters of Japanese Calligraphy. Darmstadt: Mathildenhöhe. Traveling exhibition throughout Germany. 1963 Art and Writing. Baden-Baden: Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden; Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum. Sho: Modern Calligraphy by Shiryū Morita. New York: Mi Chou Gallery. 1964 Solo exhibition. Morita Shiryū. Kyoto: Gallery of Kyoto Prefecture and Yamada Gallery.

Contemporary Japanese Painting. Washington DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art. Traveling exhibition throughout the US. 1965 Solo exhibition. Frankfurt: Hudtwalcker Gallery.

Morita, Sugai, Iida. Hannover: Brusberg Gallery. 1966 1st Japan Art Festival. Traveling exhibition throughout the US. 1967 Expo ’67. Montreal. 2nd Japan Art Festival. Traveling exhibition throughout the US. 1968 3rd Japan Art Festival. Traveling exhibition throughout Mexico. Mutual Influences Between Japanese and Western Arts. Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art. 1969 Solo exhibition. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada. Traveling exhibition throughout Canada. 1970 Expo ’70. Osaka.

Solo exhibition. Shiryū Morita. Berlin: Haus am Lützowplatz. 1972 7th Japan Art Festival. Traveling exhibition in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. 1975 Solo exhibition. Kyoto: Asahi Gallery.

10th Japan Art Festival. Traveling exhibition in Australia and New Zealand. 1976 Sho: Modern Japanese Calligraphy. Offenbach: Klingspor Museum. 1986 Artist Today: Morita Shiryū. Kyoto: Gallery 106 at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art. 1992 Morita Shiryū and Bokubi. Kobe: Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art. 2012 One Hundred Years Since the Birth of Morita Shiryū Exhibition: World’s Art Pioneer and His Traces That the City of Toyooka, Tajima is Proud of. Toyooka: Hyogo Prefectural Maruyamagawa Kouen Museum. 2013 Power of Characters, Power of Calligraphy II: A Dialogue Between Calligraphy and Painting. Tokyo: Idemitsu Museum of Arts. New Era Creations: The Trajectory of Genbi Regarding Contemporary Art, 1952−1957. Ashiya: Ashiya City Museum of Art and History. 2016 A Feverish Era: Art Informel and the Expansion of Japanese Artistic Expression in the 1950s and ’60s. Kyoto: National Museum of Modern Art. 2017 Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the West. Honolulu: Honolulu Museum of Art. The Weight of Lightness. Hong Kong: M Plus Museum. 2018 Morita Shiryū: Calligraphy of Mind. Takarazuka: Kiyoshikojin Seichoji Museum of History and Art.

Exhibition catalog: Meaning and Symbol (Sinn und Zeichen), Darmstadt and other cities in Germany, 1962.

Exhibition catalog: Morita Shiryū solo exhbition at Mi Chou Gallery, New York City, 1963.

IV. Essay

“Morita Shiryū and Avant-Garde Calligraphy”

by Osaki Shin’ichirō

On this occasion, Shibunkaku invites Osaki Shin'ichiro, the chief curator of Tottori Prefectural Museum, to contribute an essay. This essay, based on his insight into the Japanese avant-garde calligraphy and the 1950s abstract painting, attempts to reposition Morita in the context of global art history.

* Note: Images are for illustrative purposes and do not always follow the text.

1. Introduction

The term shoga ittai (calligraphy and painting as one) suggests that there once used to be a close connection between calligraphy and painting in East Asia. However, calligraphy found itself in an awkward position when the new institutional framework of art was established during the Meiji period (1868-1912). Epitomized by Koyama Shōtarō’s assertion, “calligraphy is not art,” calligraphy and painting since then have been considered to be separate disciplines. Moreover, it seems the relationship between these practices was no longer questioned at all. This is because painting does not require written texts anymore, and despite the unprecedented popularity of calligraphy as a part of school education, the so-called world of calligraphy has grown increasingly reclusive, isolating itself into a kind of insular, protected community. Therefore, it is remarkable that calligraphy and painting miraculously approached each other, though for a brief moment, about half a century ago. Calligraphers were highly conscious of the possibilities of painting, and in return, painters learned from calligraphy.

The central figure in such an interaction was the calligrapher Morita Shiryū, whose œuvre towers among postwar art. Yet such a simple understanding of Morita overlooks the far-reaching scope and breadth of his work. If we were to examine Morita’s calligraphy from the 1960s and beyond, his relationship with Zen philosophy becomes highly significant, just as one would have to extend the analysis to the calligraphic works of ancient calligraphy masters. In the context of modern art, however, calligraphy played a critical role in the art world for about a decade in the 1950s, when Morita launched Bokubi (Beauty of Ink), a comprehensive journal of calligraphic art. Morita’s calligraphy during this period represents the pinnacle of his career in its intensity and scale. The issues I will discuss here constitute only a part of Morita’s calligraphy and theories, but I am certain that the following analysis offers insights into the great achievements of avant-garde calligraphy.

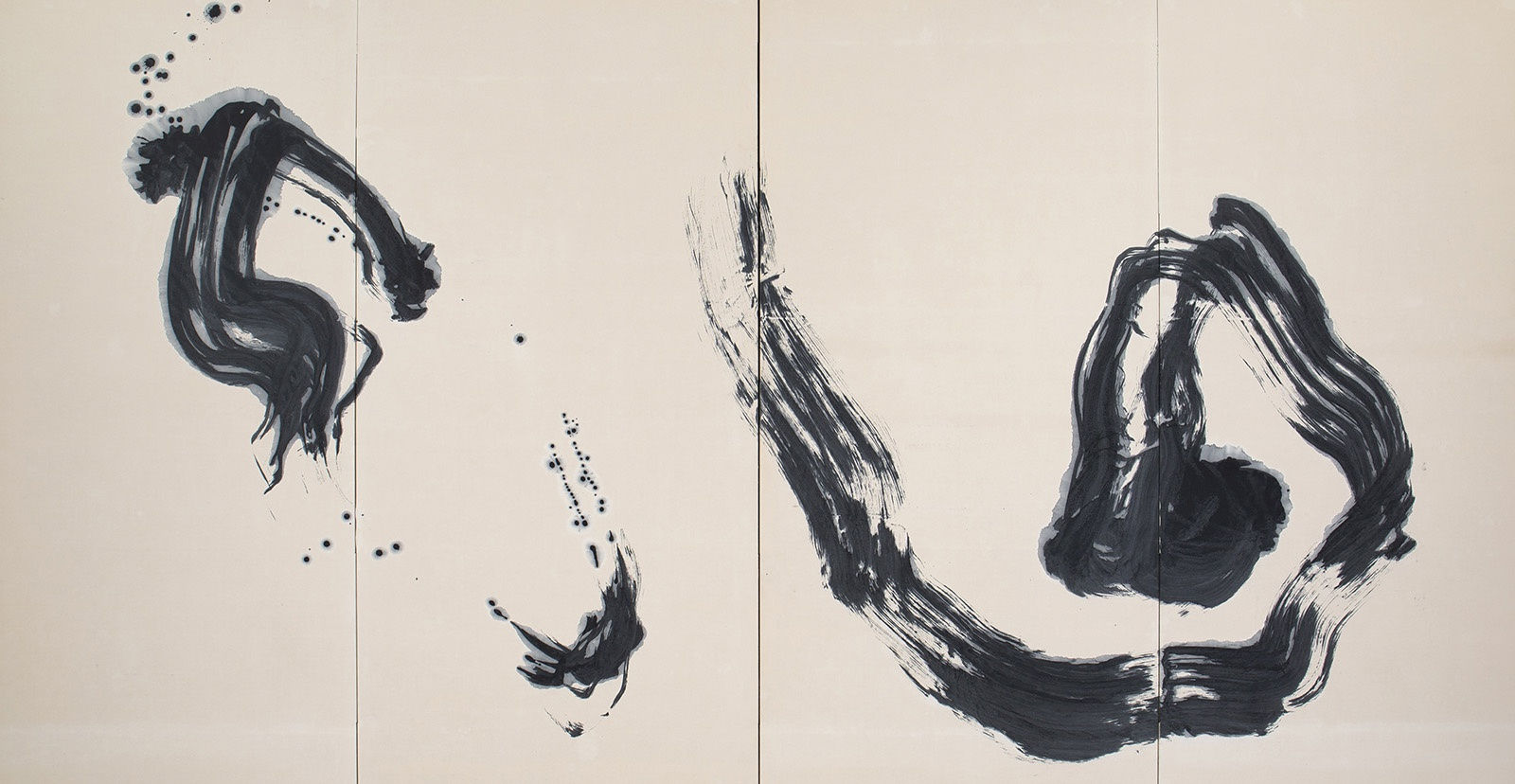

En. Ink on paper, 91 x 182 cm, 1963.

2. The Early Years, Launching of Bokubi, and Involvement in Bokujin

Morita Shiryū (real name Morita Kiyoshi) was born in Toyooka, Hyogo, in 1912. Morita was from a family of average farmers but he was blessed with supportive mentors. On recommendation of his primary school teacher Yoshikawa Isamu, who recognized his talent, Morita attended high school, which at the time was only accessible to sons of families of considerable wealth. Morita later recalled that it was Yoshikawa who introduced him to an anecdote about the Edo-period scholar Arai Hakuseki from which Morita adopted his art name Shiryū.1 After graduating from high school, the school’s principal arranged for Morita to work at the school for some time as a secretary. In 1936, he started working at the Third Kobe High School (currently Hyogo Prefectural Nagata High School) in Kobe. Morita’s transfer to a new workplace was probably due to Kondō Hideya, a well-respected principal of Third Kobe High School and a former principal of Toyooka High School. In his later years, Morita reflected on his good fortune and expressed gratitude for meeting such great mentors in his formative years.

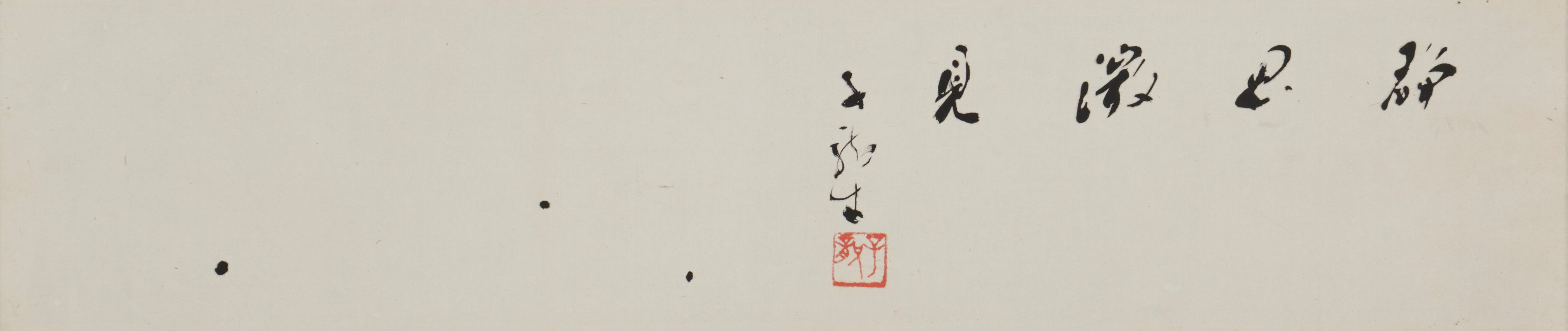

Seishi biken. Ink on paper, 14 x 68 cm, 1941.

He also had a life-changing encounter in Kobe―he met the calligrapher Ueda Sōkyū who was visiting Kobe during a lecture tour. On Ueda’s recommendation, Morita moved to Tokyo and studied calligraphy under him. Like Morita, Ueda was born in the Tajima area, the northern part of Hyogo prefecture, and had studied under Hidai Tenrai. By 1938, Ueda established Shodō Geijutsu Sha (Calligraphy Art Company) with Kaneko Ōtei and others, and built a reputation as one of the pioneering avant-garde calligraphers. It did not take long for Morita to be recognized, either. As early as 1937, a year after Morita moved to Tokyo, he exhibited at the Second Great Japan Calligraphy Society Exhibition, where he received the gold commendation award for his rinsho (free-hand copy) of Kanjōki, and won the first place among the silver awards for his original calligraphic work of a classical Chinese poem. Both works were designated as exemplary models for the Great Japan Calligraphy Society on Hidai Tenrai’s recommendation. He further received awards at the Japan-Manchuria-China Calligraphy Exhibition and the Third Great Japan Calligraphy Society Exhibition, garnering him recognition as a promising calligrapher while still in his twenties.

However, Morita fell ill during this period, presumably in 1936, as it has been mentioned that this episode had happened shortly after the February 26 Incident. Morita underwent an abdominal operation followed by another due to peritoneal adhesion. For a month before and after the operations, he suffered from high temperature and unbearable pain. For Morita, however, this hardship was a sign from heaven. Writhing in his hospital bed and thinking of ways to escape from pain, he eventually ceased to solely focus on his ailing, realizing that the pain is himself, and that he had to become one with it. He remembered: “We will be constrained by the brush if we perceive it as something on the exterior, conscious only of its usage and movements. Yet when we internalize the brush and become one with it, it will move along with the force of our life commands. In other words, I came to realize that the brush moves smoothest when I simply forget about its presence.”2 This remark closely relates to the essence of Morita’s calligraphy, especially in its divergence from the so-called automatism, and I will return to this point later.

Shadow from the Future. Ink on paper, 148 x 121 cm, 1949.

Ryū. Aluminum pigment and lacquer on paper, 24.2 x 31 cm, 1965. The character ryū (dragon) is the second character of Morita's artist name "Shiryū." It always held special significance for Morita.

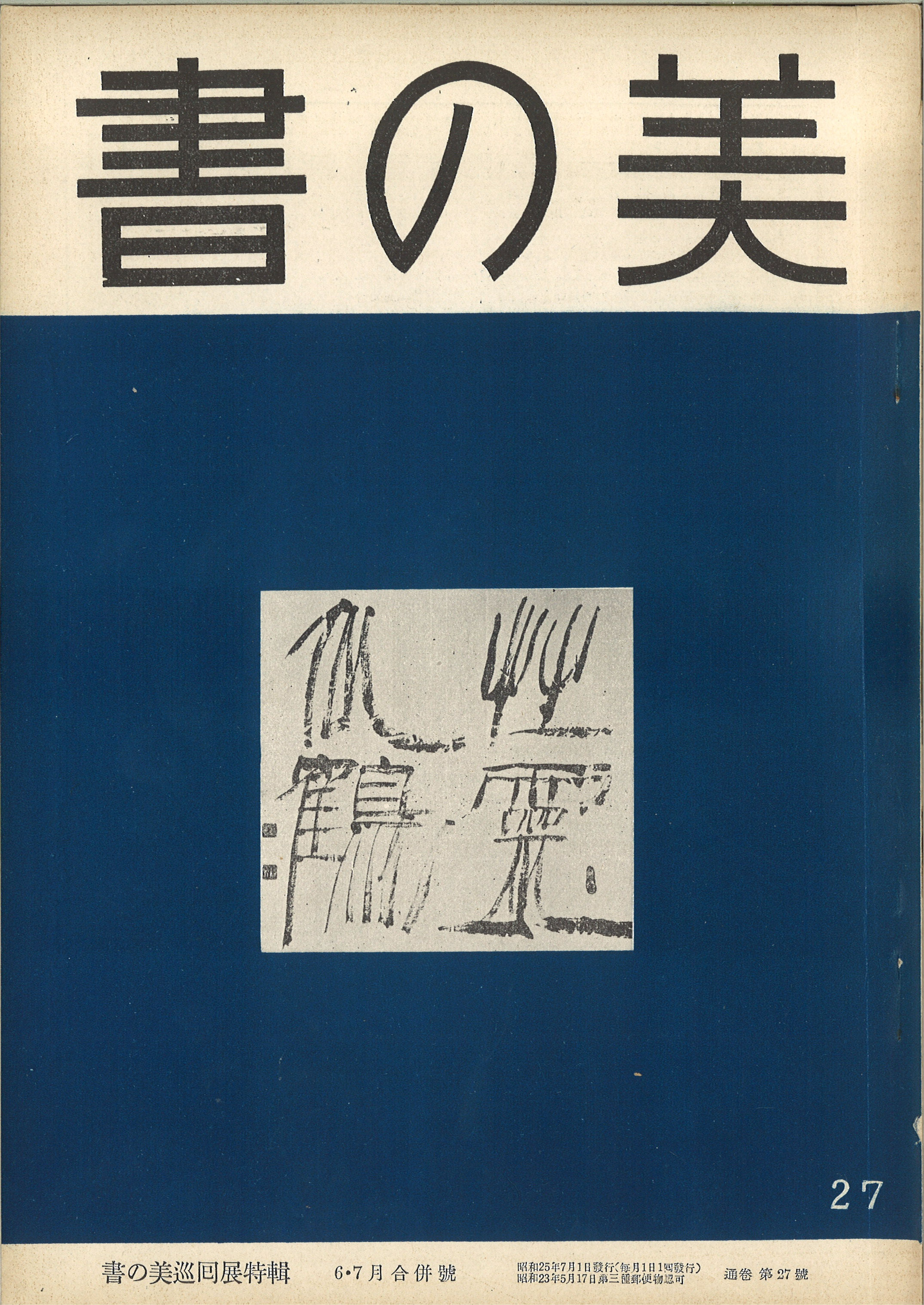

While in Tokyo, Morita edited Kenpitsu (Wielding the Brush), a calligraphy magazine for students, and Shodō Geijutsu (Art of Calligraphy), which was then a major magazine for new trends in calligraphy. Interestingly, practitioners of calligraphy at the time perceived journals as a primary medium for presenting their works, more so than exhibitions and private schools. This attitude among the practitioners is telling of the distinctiveness of the discipline, and it also had a significant impact on Morita’s career as a calligrapher. As the war intensified, Morita was forced to evacuate to his hometown in Toyooka at the end of 1944, and Ueda also evacuated to his hometown around the same time. Probably due to these circumstances, Morita started editing and publishing Sho no Bi (Beauty of Sho), a journal of Ueda Sōkyū’s school of calligraphy, in 1948. Morita recalls this time as follows:

“Although I was in the remote, northern end of Hyogo prefecture, I was boasting that this was the center of Japan. I produced calligraphic pieces for the journals, rinsho exemplars, and works for exhibitions, if there were any. I also wrote essays if necessary and enjoyed working not only as an editor but taking charge of everything. At the time, the world of avant-garde calligraphy was not fully developed yet, and it lacked any strong theoretical foundation. Seeing calligraphy in such a state was worrying me as an editor, and I gradually developed an interest in establishing a theory of calligraphy.” 3

There are two points worth pointing out in the above remark. Firstly, Morita was poignantly aware of his role as an editor at the time. It was then popular to learn calligraphy by copying exemplars in magazines and journals, and Morita was involved in several such publications as an editor. The publication of Sho no Bi ended in 1952 with the final issue 46, but its contents were continued by the Bokujin (Ink People) journal. In addition, Morita also independently launched the Bokubi (Beauty of Ink) journal in 1951. Bokujin and Bokubi will be discussed in detail in a later section, along with the Gutai Art Association’s journal Gutai, but it is worthy of note that many such “little journals” were published by artists based in the Kansai region (Western Japan) in the 1950s, and that they exerted influence not only in Japan, but to some extent also abroad. The second interesting point of Morita’s above quote is his keen realization of the need for a theory of calligraphy. This was clearly a major impetus for him to establish connections with philosophers and painters, and to launch the Bokubi journal.

Cover art of Sho no bi (no. 27, 1950)

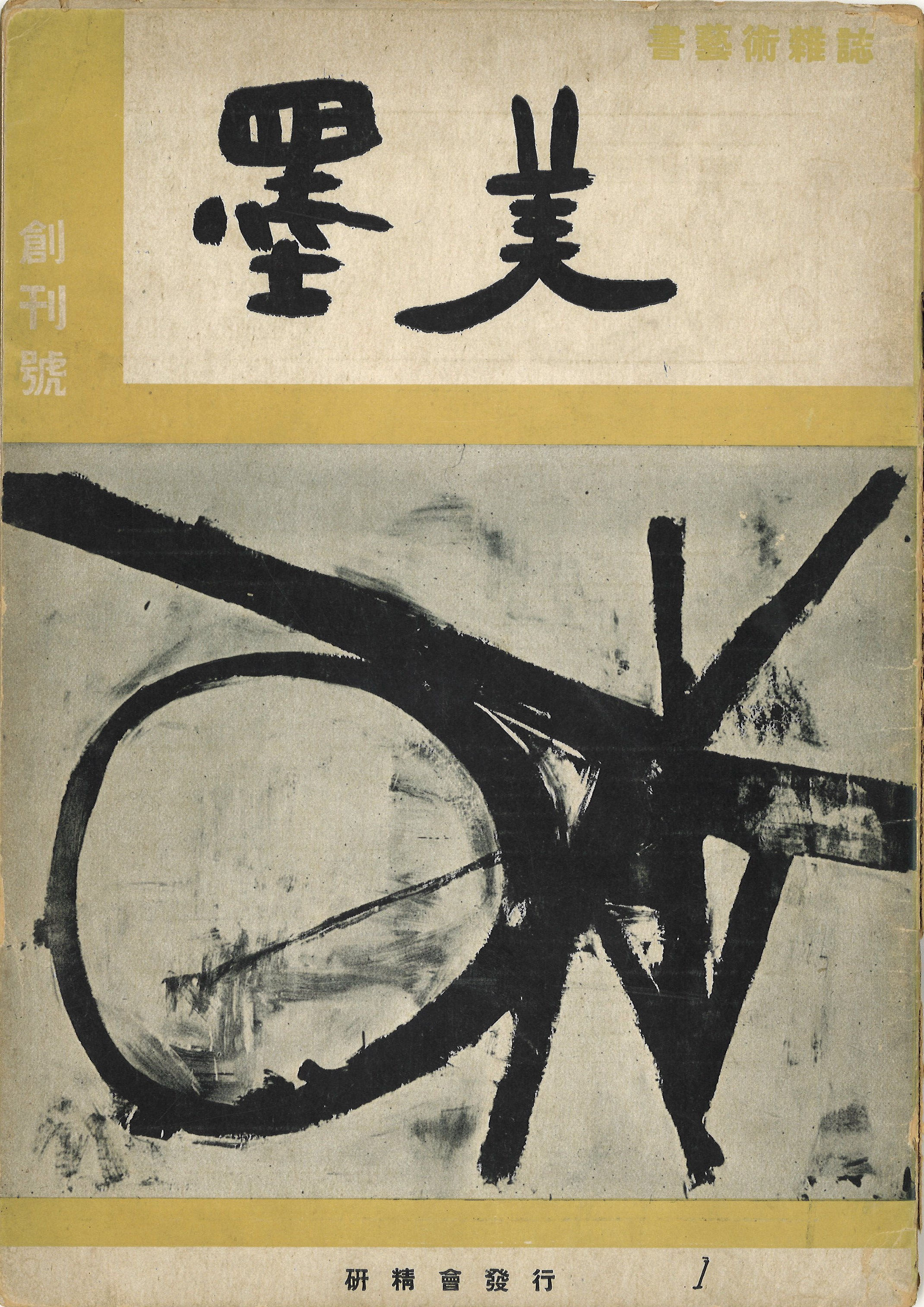

Morita moved to Kyoto in 1950. During his time in Toyooka, Morita had already made acquaintance with Ijima Tsutomu, a professor of aesthetics at Kyoto University, and had developed a fascination for the Zen philosophy of Hisamatsu Shin’ichi, so Kyoto was an ideal place to advance his style of calligraphy and its theories. Morita’s first task was to draw on his experience as an editor to launch a completely new journal, namely Bokubi, a comprehensive journal of calligraphic art first published in June 1951. Bokubi’s distinctiveness from other calligraphy journals with which Morita had previously been involved is evident in the seven objectives set out in the opening statement of its inaugural issue: “Aesthetic investigation of calligraphy; examining calligraphy within the whole human life; establishing the discipline of calligraphy based on ideas of modern art; examining calligraphy within a comprehensive perspective of art and aesthetics; expanding [East Asian] calligraphy on a global scale; reevaluation of classics; enhancing the social status of calligraphy.” Many of these goals are rooted in a concept of interdisciplinarity that seeks to reassess calligraphy by taking into consideration its relationship to different artistic disciplines, its regional character, and its role within society as a whole.

Cover of the first issue of Bokubi, featuring a painting by Franz Kline, 1951.

Cover of the first issue of Bokujin, 1952.

The period before and after Morita launched the Bokubi journal is marked by several events that had significant impact on him. In 1951, Ueda submitted a commissioned work entitled Ai (愛, love) to the Nitten exhibition. This work apparently was inspired by the sight of his grandchild crawling, although its form evokes the character hin or shina (品, refinement, goods). The perceived image, therefore, contradicts the sound that the title purports to produce. At the time, the conflict between traditionalist calligraphers and avant-garde calligraphers in the calligraphy section of Nitten was intensifying, and Ai ignited a controversy between these opposing factions. Although Ueda eventually left the Nitten, he at first sought to carry out reforms from within by remaining a member. On the contrary, Morita and other young calligraphers criticized the outmoded and closed nature of the calligraphic establishment, and advocated for a more thorough reform.

As discussed earlier, Morita spoke with gratitude of the many mentors he met in his youth, so he must have felt deeply indebted to Ueda in developing his skills and approach to calligraphy. Nevertheless, he decided to part ways with his former teacher and pursue his own path. Morita and four like-minded calligraphers―Inoue Yūichi, Eguchi Sōgen, Sekiya Yoshimichi, and Nakamura Bokushi―gathered at Ryōanji temple in Kyoto to form the Bokujinkai calligraphy group on January 5, 1952. This was accompanied by sending out letters to Ueda and other leading figures of the calligraphy circles that detailed the purposes of forming the group. Morita described these events later with strong words as themselves “rising to action.” Included in the final issue of Sho no Bi, for which Morita was the editor, are a farewell address of the five young calligraphers, directed at Ueda, and the latter’s response to it. These two letters, which reveal the strong bond between a mentor and his pupils despite expressing strong disagreements, are moving to read even today.

I realized that if I become

one with the brush, I will

achieve a more wholesome

version of myself.

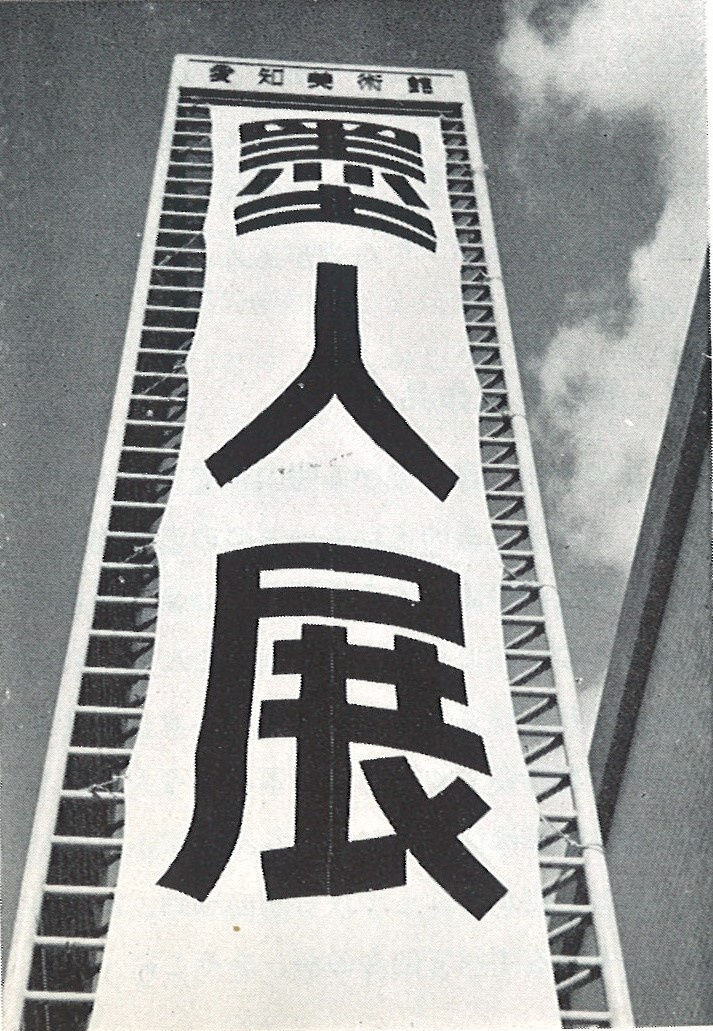

The Bokujinkai group immediately started their activities. They launched the group journal Bokujin and as early as January 1954 held the first Bokujin Exhibition at Maruzen Gallery in Kyoto. As it is easy to confuse, I would like to note again that Bokujin was published as the Bokujinkai group’s journal and was first edited by Inoue Yūichi, and from 1956 by Tsuji Futoshi. As a successor of Sho no Bi, Bokujin retained its nature as a journal that selects and reviews calligraphic works from readers.

Of particular interest is the fact that Sho no Bi’s Alpha Column, a section featuring experimental works that do not adhere to the textual nature of calligraphy, was continued in Bokujin. At Sho no Bi, Hasegawa Saburō, a painter and friend of Morita’s, was responsible for selecting and reviewing contributed works for the Alpha Column, while the editors for Bokujin’s Alpha Column included Yoshihara Jirō and other prominent abstract painters from Osaka and Kobe. The Bokubi journal, which was launched earlier, had a strong theoretical character reflecting Morita’s awareness of the issues discussed above, with many contributions from scholars and critics. The seven objectives of Bokubi have been previously mentioned, and indeed the inaugural issue of Bokubi clearly followed a course of action set out in these goals. For instance, it included a cover illustration not of a calligraphic work but an Abstract Expressionist painting by the American artist Franz Kline. It also featured a commentary on Kline by Hasegawa Saburō, and even a résumé in French at the end. There is no doubt that Morita was introduced to Kline by Hasegawa, who was fluent in foreign languages and had held solo exhibitions in the United States several times. It is uncertain whether Bokubi was sent overseas, but Inoue Yūichi at some point remarked that the journal would soon be circulated in New York.4

Notably, Japanese calligraphy attracted increasing attention in the Unites States during this period, attested by a number of calligraphy exhibitions: the Modern Calligraphy Exhibition by Shodō Geijutsuin at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1952; and the Architecture and Calligraphy of Japan Exhibition, curated by Arthur Drexler and held at the same museum the following year, included works by Morita, Ueda, Uno Sesson, and Shinoda Tōkō. Starting with Morita’s participation in Salon d’Octobre in 1953, Japanese calligraphers also began presenting works in Europe through exhibitions such as the Contemporary Japanese Calligraphy: Art in Sumi exhibition in 1955-56 that toured Amsterdam, Basel, Paris, Hamburg, and Rome, the 1957 San Paulo Biennial, and the Carnegie International Exhibition of Contemporary Paintings and Sculpture in 1958.

Installation view:

Muryōju (leftmost) by Morita exhibited at the Salon d'Octobre, Paris, 1953.Around the same time, there were many painters of then-dominant movement of Abstract Expressionism in the United States who heavily emphasized the use of strokes, just like Franz Kline, one of whose paintings was used for the cover of the first Bokubi. More interestingly, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and other leading artists in the United States in the mid-1950s seemed to compete with each other to limit the use of color in their works, resulting in an increasingly monochrome approach to abstraction. According to some anecdote, the Gutai Art Association’s journal Gutai was found in Pollock’s studio after his death. It is thrilling to think that artists in Japan, particularly those based in Kansai, were able to inspire young American artists at a time when the American continent was still far to reach. Yet there is no decisive evidence that links Japanese calligraphy to American abstract painting. In the next section, I would like to return our focus to Kansai in the 1950s, which allows for a more conclusive assessment of the relationship between calligraphy and abstract painting.

3. Background: The State of Art in Kansai

The cultural sphere of Kansai, where the cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe are located within close proximity, offers a sense of diversity that differs from that of Tokyo. Some time after Japan’s defeat in the war, and amidst reconstruction efforts, Kansai nurtured the ground for new artistic expression. Artists across the cities of Kansai and from various disciplines shared a common ground for their artistic endeavors. Firstly, Gendai Bijutsu Kondankai (Contemporary Art Discussion Group), known as Genbi, was founded in 1952, the same year the Bokujinkai group was formed. Led by Matsumura Hiroshi, who was then an art journalist at the Asahi Shinbun newspaper, Genbi’s primary activity involved monthly study groups to which a varied roster of writers, artists and critics were invited.

Around 1954: Gathering of Genbi members. Leftmost, Morita Shiryū.

Since its very first meeting, the topics of Genbi’s sessions often followed a pattern of “Modern Art and …,” making it quite clear that Genbi was intended to promote modern art across artistic disciplines in the Kansai region. Along with meetings on “Modern Art and Children’s Painting” and “Modern Art and Commercial Art,” Morita was scheduled to lecture as early as February 13, 1953, on the topic of “Modern Art and Calligraphy.” A transcript of this meeting is featured in issue 12 of Bokujin, published in April 1953. In addition to the founding members of Bokujinkai such as Morita and Inoue Yūichi, attendees included painters such as Yoshihara Jirō, Tsutaka Waichi, Suda Kokuta, and Shimamoto Shōzō, and the sculptor Horiuchi Masakazu, indicative of their keen interest in calligraphic expression. Genbi also held five exhibitions entitled Genbi-ten (Genbi Exhibition) in different locations of the Kyoto-Kobe-Osaka area, spanning the years 1953 to 1956. In addition to paintings and sculptures, the Genbi Exhibitions featured a variety of media encompassing calligraphy, crafts, industrial design, fashion, and ikebana. Bokujin reported on the first Genbi Exhibition in issue 18, and in turn, served itself as a platform to promote such interdisciplinary interactions. For instance, transcriptions of important lectures and roundtable talks were published in Bokujin, while the Alpha Column, succeeded from the Sho no Bi journal, was renamed the Painting Column in 1953, with abstract painters including Yoshihara Jirō, Suda Kokuta, and Tsutaka Waichi selecting the contributions. Just like Franz Kline’s work was featured on the cover of Bokubi, Bokujin’s covers included abstract paintings by Yoshihara Jirō and Shimamoto Shōzō.

Installation view: Genbi Exhibition of 1954.

I have previously mentioned that Genbi was not only a study group but also involved itself in the planning and organization of exhibitions. These Genbi Exhibitions, held five times in museums and department stores in Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe between 1953 and 1957, displayed works of a variety of media alongside each other, with dresses and ikebana works placed among paintings and three-dimensional objects. Resembling a kind of mixed martial arts presentation, the exhibitions deeply inspired artists, and led calligraphers to recognize the urgent need for a sense of presence that withstood the large paintings next to which they were displayed. Interestingly, many abstract painters in Kansai during this period produced monochrome works with emphasized brushstrokes that clearly leaned into the domain of calligraphic abstraction. Yoshihara Jirō, who later produced calligraphy-like works with a white circle against a black background (although the intentions are completely different), was at the time creating a series of paintings characterized by incisive brushstrokes with a strong sense of materiality.

Hasegawa Saburō, Nakamura Shin, Suda Kokuta, and other painters who closely interacted with calligraphers also produced works that express a striking visual affinity with calligraphy. It is easy to guess that behind such developments were the previously mentioned interdisciplinary study groups, roundtable talks, and publication of journals. But why were the painters interested in the vigorous brushwork and dynamism characteristic of calligraphy in the 1950s? In the first half of the 1950s, representational painting reflecting and commenting on current social issues, known as “reportage painting,” was thriving in Tokyo, while abstract painting was prevalent in Kansai. Artists in Kansai, concerned with advancing a modernist approach to art, tackled challenging question such as how to overcome Cubism and the abstract styles that followed. Although Picasso’s Analytic Cubism and Mondrian’s geometric abstraction count as the pinnacles of modernist painting, both the Cubist facets and Mondrian’s grids petrified the pictorial surface, resulting in an impasse for the discipline of painting. The bold brushstrokes of calligraphy, therefore, were instrumental in liberating the pictorial surface once again.

As early as in 1952, issue 14 of Bokubi featured a discussion by Morita, Yoshihara, and Suda on the calligraphy of Nantenbō, a Zen priest based in Nishinomiya, Hyogo. According to Yoshihara, Nantenbō’s calligraphy had the potential of overcoming the rigidness of modernist painting because it was based on the temporality of the moment when wielding the brush. This notion of temporality was thoroughly pursued not so much by Yoshihara himself but by younger artists such as his pupils Shiraga Kazuo and Shimamoto Shōzō. It was around this time, in late 1954, when young avant-garde artists who joined Yoshihara’s cause formed the Gutai Art Association, and their early works are today enshrouded by an aura of what might be called a mythology of modern art. During this period, they carried out numerous unprecedented experiments, such as “actions” (painting performances), outdoor exhibitions, and even exhibitions on theater stages. Gutai action paintings in particular are today considered as a consequential departure from those of Pollock. As seen in Shiraga’s foot paintings and Shimamoto’s bottle-throwing paintings, their “actions” provided a critical opportunity for Gutai artists to break through the rigid pictorial surface, and introduce a new dynamism to it. I believe they found a way to achieve this through interactions with Morita and other calligraphers.

Bokujin Group Exhibition banner, 1960.

We might ask in return: what possibilities did the interactions with painters open up for calligraphers? By showing calligraphy at exhibitions alongside other types of artwork, avant-garde calligraphers realized the potential of calligraphy as an art form for large public spaces, rather than as a private occupation carried out at home and in classrooms like rinsho (copying from exemplary works or old masters) or when submitting calligraphy for the competitions held by magazines and journals. They enlarged the size of their works to achieve a sense of physical presence that would put them on par as works of art when displayed in an art museum. It should be pointed out that pioneering works of Japanese avant-garde calligraphy by those like Teshima Yūkei and Hidai Tenrai were exceptionally large. At the same time, the calligraphers established an approach called shōjisū-sho, which is usually limited to only one or two characters per composition. In conventional calligraphy, the writer would render a whole passage or sentence from a given text, so the act of reading and the relationship of one characters to the other in a sequence is of importance. However, single- or two-character compositions are linked to the act of looking, hence its potential to be read visually as an image. The emergence of this style is not only related to the issue of scale but the question of whether calligraphy should be regarded as a set of characters or an image—a problem which strikes at the heart of ink abstraction.

Moreover, Morita and Inoue experimented with mixing ink and materials foreign to calligraphy, such as lacquer, pigments, and glue to create calligraphic works with a pronounced sense of materiality. As a result, the works of Morita and Inoue produced at the time easily bear comparison with abstract paintings of their contemporaries in terms of their presence and intensity. Calligraphy had at last achieved a strength that equaled that of painting. I have previously mentioned that Japanese calligraphy was widely introduced to Europe and the United States in the 1950s, and that domestic exhibitions of modern art often included a section on “ink abstraction,” allowing paintings and calligraphic works to be displayed in places of equal prominence. These conditions surrounding calligraphy were a natural outcome of the interrelated nature of abstract painting and avant-garde calligraphy at that time.

4. Calligraphy and Abstract Painting

Since the publication of Morita Shiryū Catalogue Raisonné, 1952-1998 it has become possible to study almost his whole œuvre at a glance. As mentioned earlier, Morita’s calligraphy from the 1950s is unparalleled in its scale and intensity, even when compared to his peers within the context of avant-garde calligraphy. But Morita did not rest there. The reason why Morita took a new departure relates to the intrinsic nature of calligraphy as an artistic expression. In my view, avant-garde calligraphy and abstract painting circles in the 1950s were highly aware of each other, as if seeing their counterpart as their own mirror image. Abstract painters envisioned in avant-garde calligraphy new possibilities of painting to come, while avant-garde calligraphers reinforced their works by taking inspiration from abstract paintings. Despite such back and forth between the two disciplines, Morita knew that there was a difference between calligraphy and painting and that by its very nature calligraphy could achieve things that were different from the possibilities of painting. For modernist painters, “action” meant to deliver a blow to destroy the hitherto unassailable pictorial surface. Murakami Saburō, a Gutai member, literally broke through the pictorial surface with his own body during his kami-yaburi (paper-breaking) performances.

Meanwhile, Abstract Expressionists in the United States sought to reinvigorate painting by more moderate means, introducing a sense of the accidental through automatism, an approach borrowed from the Surrealists. Jackson Pollock is a typical example: In his “poured paintings,” the all-over composition derived from Cubism and the Surrealist automatism are united exquisitely. Other examples might be the paintings by de Kooning and Kline whose strokes overwhelm the pictorial surface, with a strong reliance on the accidental. With its dynamic movements, splashes, and drips Morita’s calligraphy may seem to share many similarities with these styles. However, there is a crucial difference. Although Inoue Yūichi’s works at the time abandoned calligraphy’s textual nature, Morita never distanced himself from characters. If one regards calligraphy not in terms of its readability but its visuality, the textual nature of calligraphy could be a hindrance. In fact, Yoshihara advised calligraphers as follows: “I have become increasingly aware that the massive restriction of calligraphy lies in its textual nature. Yet I wonder if calligraphy must adhere so rigidly to characters. Maybe this restriction needs to be sacrificed in order to achieve a deeper level of creativity, even though I think that calligraphy has already come a long way.”5 It is a statement telling of Yoshihara as a modernist, but Morita in turn thought it is instead the painters who are swayed too much by the notion of that creativity. He later described in an interview with me, “The important thing is to not hinder the movement of one’s inner life by thinking about shapes and forms. Ultimately, what lay expansively before us are the dynamic force of life, or the reflection of the artist’s rich, true self, beyond visible forms.”6

Calligraphy demonstration in Germany: Article from local newspaper, Darmstädter Tagblatt, Darmstadt. May 7, 1962.

In another essay, Morita wrote critically about Western abstract painting, including that by Kandinsky and Mondrian, and he extended his views also to Pollock: “He has spread out the canvas on the floor, but his dripping brush just kept moving―from the inside to the outside, and from the outside to the inside of the realm of the canvas―regardless of the limits of its surface. His movements, which have neither a fixed nor definite place, had no choice but to scatter without restraint… He cannot reflect upon himself with the canvas's surface as his place, and in turn his movements, moment by moment, fail to imbue themselves with new life. His lines and shapes, the results of his movements, do not deepen their quality either.”7 It is a scathing statement, but one wonders what was the reason for Morita’s strong belief in the superiority of calligraphy over abstract painting. It might have derived from, ironically, the very textual nature of calligraphy that Yoshihara saw as a constraint. Morita’s approach was distinct from the Surrealist automatism and the actions frequently employed by Gutai artists, despite their shared common features. In contrast to the expansive lines and forms of abstract painting that could never be deepened in quality, calligraphy relies on characters as its very framework. What constitutes the framework to which Morita refers to is, on the one hand, a spatial limitation imposed by the use of characters, and on the other hand, its temporality.

In Morita’s single-character works from that time, for instance Tō (凍) or Datsu (脱), we recognize their unwavering presence as texts, but also the fact that they are embedded in temporality. One of the points that Yoshihara criticized about Mondrian’s paintings was that it is difficult to determine how much time was spent to produce them. To paraphrase this, we cannot discern in what order the brushstrokes of action paintings are executed, while in avant-garde calligraphy we could instantly infer the movements of brush and follow its paths. This is because, as a general rule, every character has a stroke order, and these strokes are normally written from left to right and from top to bottom. Therefore a precise order and temporality is inherent in every work, even if it only consists of a single character. Admittedly, calligraphy is constrained by its textual nature. For Morita, however, this was not a real constraint. The very understanding of calligraphy’s textual nature as a constraint reveals, though unexpectedly, the fact that one’s own thinking is still within the constraints of shape and form. Avant-garde calligraphy is defined by characters as its framework, and its temporality, which articulates an irreversible flow of time that cannot be replicated. While a brushstroke in action painting can be painted over, a stroke in calligraphy cannot be redone or corrected. Morita’s calligraphy is accomplished in a single session, and he likened this impossibility of replication to the life of a calligrapher who only lives once.

Calligraphy demonstration: Performance during Morita's stay in New York City, 1963.

Therefore, he understood the degree of completion in calligraphy as a mirror of in the calligrapher’s life. In a Bokujinkai workshop in 1961, Morita concluded: “The beauty of calligraphy lies in the reflection of one’s true self, which is actualized through the characters, composed by brush, ink, and paper.”8 This relates to the notion of “the movement of one’s inner life,” which I touched upon earlier. Morita now shifted his focus from “calligraphy as an object” to “the calligrapher as a subject.” As if echoing this idea, the Bokubi journal, which devoted many pages to discussions of abstract paintings in the 1950s, started featuring articles on the writings of old masters and the calligraphy of their predecessors. This moment marked the end of a brief romance between calligraphy and abstract painting. Although Morita continued producing works rife with intensity, his approach was no longer based on the idea of advancing calligraphy through competition with other artistic disciplines or avant-garde art in the United States and Europe, as he sought at the time of Bokubi ’s inauguration. Instead, he had arrived at an essentialist and spiritualist approach. However, Morita’s works from the 1960s onwards, which are often associated with Zen philosophy, are beyond the scope of our discussion and call for a different perspective.

(Osaki Shin’ichirō, Deputy Director of Tottori Prefectural Museum)

Notes

1. Morita Shiryū, “Sho, Writing and Thinking over the Last Six Decades [Sho, kaite kangaete 60-nen]” in the exhibition catalog Morita Shiryū and Bokubi, Hyogo Prefectural Modern Museum of Art, 1992, p. 4.

2. Ibid., p. 7.

3. Ibid., p. 7.

4. Inoue Yūichi, “Reading Kline’s Letters [Kurain shi no tegami o yonde]” in Bokujin, May 1952, p. 2.

5. Yoshihara Jirō, Round-table talk “Calligraphy and Abstract Painting [Sho to chūshō kaiga]” in Bokubi, August 1953, p. 5.

6. “Interview: On Calligraphy and Abstract Painting,” interviewer Osaki Shin’ichirō, in the exhibition catalog Morita Shiryū and Bokubi, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, 1992, p. 4.

7. Morita Shiryū, Sho to Bokushō [Calligraphy and Ink Art], Shibundō Publishing, 1975, p. 59.

8. Morita Shiryū, “The Beauty of Sho [Sho no utsukushisa]” in Recollections and Notes on Morita Shiryū [Sōki: Morita Shiryū nōto], Bokujinkai Soryusha, 2013, p. 177.

Ekō. Ink on paper, 139 x 267 cm, 1967.

Kumo mushin. Ink on paper, 141 x 280 cm, c. 1967

Acknowledgements

Footage and photos courtesy of Soryushua.

Photo of Genbi meeting c.1954, courtesy of Otani Memorial Art Museum

Special thanks to Inada Sousai, Bokujinkai.